Belangengroep Multiple Endocriene Neoplasie (NL)

Multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1) syndrome is also known under the name of Wermer’s syndrome. It is a hereditary disease that can affect the endocrine system through development of neoplastic lesions in the pituitary, parathyroid gland and pancreas. This in turn leads to excess productions of associated hormones, which may cause symptoms.

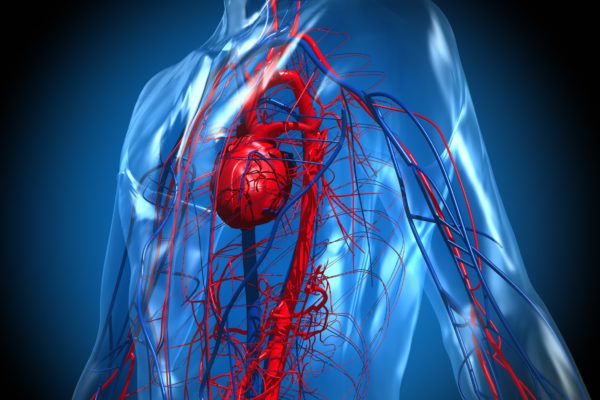

Hormones are chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream and regulate the function of cells and tissues throughout the body. MEN involves tumours in at least two endocrine glands; tumours can also develop in other organs and tissues. These growths can be non-cancerous (benign) or cancerous (malignant). The two major forms of multiple endocrine neoplasia are called type 1 and type 2. Type 1 and type 2 are distinguished by the genes involved, the types of hormones made and the characteristic signs and symptoms. If the tumours become cancerous, some cases can be life-threatening. The disorder affects 1 in 30,000 people.

Although many different types of hormone-producing tumours are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia, tumours of the parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, and pancreas are most frequent in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Many patients also display benign growths, such as lipomas, collagenomas and angiofibromas. Around half of patients develop a tumour in the hormone-producing part of the pancreas and the duodenum. These tumours are known as neuro-endocrine tumours or NETs. Click here to read more information on NET. Around 25 to 50% of patients will have tumours in the adrenal gland, though these are almost always non-malignant. Click here to read more on adrenal gland cancer.

Most MEN1 patients will, at some stage, develop tumours in the parathyroid glands. Half of patients develop tumours around the age of 25, and 90% of 50-year-old patients will have these tumours. They are almost always non-malignant but they do cause hyperparathyroidism, which causes elevated calcium levels in the blood. Click here for more information on pituitary gland cancer.

Besides these frequently occurring growths, there can also be tumours in the stomach, lungs or thymus. These organs contain cells that produce hormone-like substances. When these cells grow into tumours they are known as carcinoid tumours. These occur less frequently, accounting for only 10% of all MEN1 patients. Tumours associated with MEN1 aren’t always malignant, but most of those that develop in the stomach, pancreas or thymus are.

It is impossible to predict which type of tumour will develop in MEN1 patients. Therefore, there are lots of different symptoms involved, depending on where the tumour is situated.

Patients who develop parathyroid gland cancer can present:

Patients with carcinoid tumours only develop symptoms when the tumour starts to grow into adjacent tissue. This can cause chest pains and breathing difficulties.

The MEN1 syndrome is caused by a fault in the patient’s genes. Specifically the MEN1 gene, which is located in chromosome pair 11. The MEN1 gene is associated with the production of menin. This protein blocks cells from dividing when there is no need for it and as such represses tumour growth. Because this gene is impaired in patients with MEN1, menin production is hampered, causing inadequate suppression of tumorous growths.

To distinguish between the MEN1 symptoms and merely having a genetic disposition to develop MEN1, a clinical diagnosis is needed. When a patient has a clinical diagnosis MEN1, it means that the disease has manifested itself in an unmistakable manner. To confirm the diagnosis, the endocrinologist will ask questions about the patient’s family history. To find out whether a person carries the faulty gene, genealogical research is necessary as well as a DNA test.

If this research leads to a clinical diagnosis, or the discovery of the faulty gene, the patient will be advised to undergo regular check-ups, so that possible tumours can be detected at an early stage. Children as young as 5 years old can be checked for MEN1 if their family history requires it. During examination, doctors will ask after general health complaints and also perform blood tests, with special focus on calcium, gastrin, prolactin and IGF-1 levels. When any abnormalities show up in these tests, a CT scan, an MRI scan or ultrasound may follow.

A GP will recommend patients over the age of 15 to undergo scans every two years to examine their thyroids, adrenal glands and pancreas. Every three years, the chest cavity is also examined, in order to detect tumours at an early stage.

If one or more tumours have been found, a team of specialists come up with a treatment strategy, depending on the type and stage of the cancer. For specific information on treatments, please read the chapters for the relevant cancers.

In case of a tumour in the parathyroid glands, a surgeon may remove these glands partly or entirely. Should all four parathyroid glands need to be removed, the surgeon may transplant a healthy part of one of these into the lower arm. If necessary, the thymus may also be removed. When a patient has been diagnosed with one or more carcinoid tumours, surgery, chemotherapy or radiation are all options that can be considered. These tumours do not have a very good outlook when they appear in the thymus, as they tend to be discovered at a very late stage. If a carcinoid tumour appears in the lungs, growth tends to be very slow. In these cases, doctors often opt for expectant management of the tumour.